From Wikipedia

Open on Wikipedia

| Venezuelan troupial | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Icteridae |

| Genus: | Icterus |

| Species: | I. icterus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Icterus icterus (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Oriolus icterus Linnaeus, 1766 | |

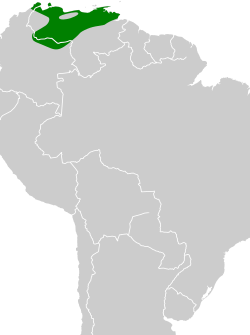

The Venezuelan troupial, known in Venezuela as the Turpial[2] (Icterus icterus), is the national bird of Venezuela. It is found in Colombia, Venezuela, and the Caribbean islands of Aruba, Curaçao, Bonaire, Trinidad, and Puerto Rico. Together with the orange-backed troupial and campo troupial, it was previously part of a superspecies simply named the troupial that was split.

Name

[edit]The term troupial is from French troupiale, from troupe ("troop"), so named because they live in flocks.[3] The Latin name icterus is from Greek ἴκτερος (íkteros, "jaundice"); the icterus was a bird the sight of which was believed to cure jaundice, perhaps the Eurasian golden oriole.[4] It also had the more general meaning "yellow bird", which is why the name was later given to this South American bird.[5]

Description

[edit]Venezuelan troupials are fairly large in size, with a long tail and a bulky bill. It has a black head and upper breast. The feathers on the front of the neck and upper breast stick outward, making an uneven boundary between the black and the orange of the bird's lower breast and underside. The rest of the orange color is found on the upper and lower back, separated by the black shoulders. The wings are mostly black except for a white streak that runs the length of the wing when in a closed position. The eyes are yellow, and surrounding each one, there is a patch of bright, blue, naked skin.

Subspecies

[edit]There are three subspecies: I. i. icterus, I. i. ridgwayi, and I. i. metai. Individuals of I. i. metae have more orange on the back and a black line that divides the lengthwise white wing-stripe in half. Individuals of I. i. ridgwayi are generally stronger and larger in proportion to the other subspecies.

Habitat

[edit]

Venezuelan troupial inhabit dry areas like woodlands, gallery forest, dry scrub, plains, and open savanna, where they mainly forage for fruits of the giant cactus, which make up their entire diet while in season. However, they also consume other fruits, such as mangoes, sapodillas, papaya, soursop, dates and malpighia cherries. They have also been known to eat the juvenile birds and unhatched eggs of the nests they attack.[6]

Breeding

[edit]Venezuelan troupials breed from March to September. They do not construct their own nests, but are instead obligate nest pirates. They make no nest of their own, but must instead either find a vacant nest or drive the adults away from an active nest. Venezuelan troupials are capable of violent attacks against established nesters. Upon taking over a nest, they may eat any eggs or young nestlings remaining in the newly acquired nest, and will fiercely defend the area against would-be intruders. Eventually the adult troupials go on to produce their own clutch of three to four eggs that hatch after about two weeks of incubation.

Behavior

[edit]Their mating behavior can be expressed as defensive in both males and females. Although males usually sing as a sign of attracting females or defending themselves from unwanted/competing troupials.[7] Duetting behavior in these particular birds is meant to defend their territories and maintain contact (communication). Males also approach this behavior during paternity guarding contexts, as this species' behavior is consistent in breeding and nonbreeding seasons. Their defending behavior was exclusively related to troupials having couples, as their partners usually elicit stronger vocals and physical responses.

In culture

[edit]The Venezuelan troupial, as the national bird of Venezuela, appears on the reverse side of the Venezuelan Bs.S 500 banknote.

Former Miss International Edymar Martínez wore the image as a national costume in 2015 in Tokyo, Japan.

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Icterus icterus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018 e.T22735310A132036720. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22735310A132036720.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Ardeola. Ardeola.

- ^ "Definition of TROUPIAL". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ ictĕrus in Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short (1879) A Latin Dictionary, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ "Definition of Icterus". MedicineNet.

- ^ "The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago - Icterus icterus (Troupial)" (PDF). uwi.edu.

- ^ Odom, K. et al., (2017, August 11) Duetting behavior varies with sex, season, and singing role in a tropical oriole (Icterus icterus) Behavioral Ecology, 28 (5), 1256–1265. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arx087

- Jaramillo, Alvaro and Burke, Peter, New World Blackbirds: The Icterids (1999), ISBN 0-691-00680-6.

- Ridgely, Robert S., and Tudor, Guy, The Birds of South America: Volume 1- The Oscine Passerines (1989), ISBN 0-292-70756-8.

- Odom, K. et al., (2017, August 11) Duetting behavior varies with sex, season, and singing role in a tropical oriole (Icterus icterus) Behavioral Ecology, 28 (5), 1256–1265. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arx087

- Burke and Jaramillo 1999; Ridgely and Tudor 1989

External links

[edit]- Troupial - Animal Diversity Web