From Wikipedia

Open on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2010) |

| Audubon's oriole | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Icteridae |

| Genus: | Icterus |

| Species: | I. graduacauda

|

| Binomial name | |

| Icterus graduacauda Lesson, 1839

| |

| |

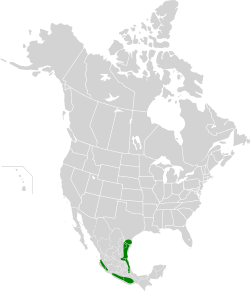

Audubon's oriole (Icterus graduacauda), formerly known as the black-headed oriole, is a New World passerine inhabiting the forests and thickets of southeastern Texas and the Mexican coast. It is the only species to have a black hood and yellow body. It is divided into four subspecies and two allopatric breeding ranges. The westernmost range extends from Nayarit south to southern Oaxaca, whereas the eastern range stretches from the lower Rio Grande valley to northern Querétaro. The most common in the western range are the subspecies I. g. dickeyae and I. g. nayaritensis; I. g. graduacauda and I. g. audubonii can be found in the eastern range. Like most Central American birds, it is not a migratory species and does not display significant sexual dimorphism. DNA analysis of the ND2 and cyt-b genes strongly suggests that I. graduacauda is most closely related to I. chrysater, the yellow-backed oriole.[2] It is a member of the genus Icterus and therefore should not be confused with the Old World orioles.

Description

[edit]The male of the species has a black hood, mandible, and throat, as well as a black tail. Wings are black, but the remiges and rectrices (flight feathers) are fringed with white. The secondary coverts form yellow epaulets. The back and vent are yellow washed with olive, and the underside is almost uniformly yellow. Females of this species have a slightly more olive nape and back than the males. The adult female's plumage is similar to the juvenile plumage; however, unlike adults, the wings are dull brown instead of black. In general, immature specimens have the hood; wingbars; remiges; and epaulets of adult specimens. The first-basic plumage retains the darker, greener coloration of the juvenile plumage, however. Molting generally occurs in early autumn, though some specimens have been noted to molt as early as June.

Subspecies dickeyae

[edit]The subspecies I. g. dickeyae is of note because of the differences in appearance, behavior, and phylogeny between it and the other subspecies of I. graduacauda. The olive wash is weaker, making the bird more proportionally yellow than others of its species. In addition, the yellow epaulets are diminished in dickeyae, being confined to the lesser coverts. This subspecies is endemic to high altitude pine forests is western Mexico.

Behavior

[edit]Audubon's oriole inhabits dense evergreen forests and thickets, preferring riparian (riverside) areas. Though it prefers the shade, mating pairs may occasionally spotted foraging in clearings. In flight, it joins mixed-species flocks that include orioles, jays, tanagers, and other birds of similar size. It forages in dense vegetation, often near forest clearings.[3]

Reproduction

[edit]The nest of the Audubon's oriole is similar in size and construction to those of the hooded and orchard orioles, being approximately three inches in diameter with a similar depth. It resembles a hanging pouch or basket, not as deep as other species'. The rim is firmly woven to the supporting twigs and the entrance is somewhat constricted. The nest itself is usually composed of long grass stems, woven while they are still green and lined with finer grass.[4]

A mating pair of orioles usually incubates two broods per year, each consisting of between three and five eggs per brood; however, chicks hatched from the later brood are usually unable to survive the winter. This species' nests are often a popular choice of parasitization by the Brown-headed cowbird.[3]

Voice

[edit]The song of the Audubon's oriole is a series of slow, slurry whistles. Its calls include a nasal "ike, ike, ike" and a whistled "peu".[5]

Diet

[edit]It inserts its bill into soft dead wood or plants and uses its beak to force said plant open to expose insects hiding inside. It feeds on insects, spiders, fruits, and also accepts sunflower seeds from bird feeders.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2020). "Icterus graduacauda". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22724081A138250610. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22724081A138250610.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Omland, Kevin E.; Lanyon, Scott M.; Fritz, Sabine J. (1999). "A Molecular Phylogeny of the New World Orioles (Icterus): The Importance of Dense Taxon Sampling". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 12 (2): 224–39. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0611. PMID 10381325.

- ^ a b c "Audubon's oriole, Life History". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ "Audubon Field Guide". National Audubon Society. 13 November 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ "Audubon's Oriole Sounds, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology".

Further reading

[edit]- Bent, Arthur Cleveland (1965). Life Histories of North American Blackbirds, Orioles, Tanagers, and Allies. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-21093-6.

- Jaramillo, Alvaro; Burke, Peter (1999). New World Blackbirds: The Icterids. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00680-2.

- Peterson, Roger Tory; Chalif, Edward L. (1973). A Field Guide To Mexican Birds. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-395-97514-5.

- Stutchbury, Bridget J. M. & Morton, Eugene S. (2001). Behavioral Ecology of Tropical Birds. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-675556-5.

- Baker, Jason M.; López-Medrano, Esteban; Navarro-Sigüenza, Adolfo G.; Rojas-Soto, Octavio R. & Omland, Kevin E. (2003). The Auk.

- Flood, N. J.; J. D. Rising & T. Brush (2002). "Audubon's Oriole (Icterus graduacauda)". In A. Poole & F. Gill (eds.). The Birds of North America. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Birds of North America.

- Flood NJ. (1990). Aspects of the Breeding Biology of Audubon's Oriole. Journal of Field Ornithology. vol 61, no 3. p. 290-302.

- Hobart HH, Gunn SJ & Bickham JW. (1982). Karyotypes of 6 Species of North American Blackbirds Icteridae Passeriformes. Auk. vol 99, no 3. p. 514-518.

- Monk S. G. M.S. (2003). Breeding distribution and habitat use of Audubon's oriole in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. The University of Texas - Pan American, United States.

- Patrikeev, Michael, Jack C. Eitniear, Scott M. Werner, Paul C. Palmer (2008) Interactions and Hybridization between Altamira and Audubon's Orioles in the Lower Rio Grande Valley Birding 40(2):42-6

About

No page comments added.Synonyms

- AUOR