From Wikipedia

Open on Wikipedia

| Black-tailed godwit | |

|---|---|

| |

| In breeding plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Limosa |

| Species: | L. limosa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Limosa limosa | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

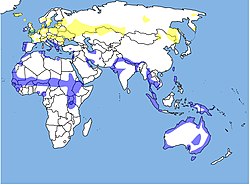

| Range of L. limosa Breeding range Resident range Wintering range

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa) is a large, long-legged, long-billed shorebird first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. It is a member of the godwit genus, Limosa. There are four subspecies, all with orange head, neck and chest in breeding plumage and dull grey-brown winter coloration, and distinctive black and white wingbar at all times.

Its breeding range stretches from Iceland through Europe and areas of central Asia. Black-tailed godwits spend (the northern hemisphere) winter in areas as diverse as the Indian subcontinent, Australia, New Zealand, western Europe and west Africa. The species breeds in fens, lake edges, damp meadows, moorlands and bogs and uses estuaries, swamps and floods in (the northern hemisphere) winter; it is more likely to be found inland and on freshwater than the similar bar-tailed godwit. The world population is estimated to be 634,000 to 805,000 birds and is classified as Near Threatened. The black-tailed godwit is the national bird of the Netherlands.

Taxonomy

[edit]The black-tailed godwit was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Scolopax limosa.[3] It is now placed with three other godwits in the genus Limosa that was introduced by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in 1760.[4][5] The name Limosa is from Latin and means "muddy", from limus, "mud".[6] The English name "godwit" was first recorded in about 1416–17 and is believed to imitate the bird's call.[7]

Four subspecies are recognised:[5]

- L. l. islandica – Brehm, 1831: the Icelandic black-tailed godwit, which breeds mostly in Iceland, but also on the Faeroe Islands, the Shetland and the Lofoten Islands. It has a shorter bill, shorter legs and more rufous coloration extending onto the belly, compared to L. l. limosa.[8]

- L. l. limosa – (Linnaeus, 1758): the European black-tailed godwit, which breeds from western and central Europe to central Asia and Asiatic Russia, as far east as the Yenisei River.[9] Its head, neck and chest are pale orange.[8]

- L. l. melanuroides – Gould, 1846: the Asian black-tailed godwit, which breeds in Mongolia, northern China, Siberia and Far Eastern Russia.[9] Its plumage is similar to L. l. islandica, but is distinctly smaller.[8]

- L. l. bohaii – Zhu, Piersma, Verkuil & Conklin, 2020:[10] assumed to breed in Russian Far East; non-breeding in northeast China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Peninsular Malaysia

Description

[edit]

The black-tailed godwit is a large wader with long bill (7.5 to 12 cm (3.0 to 4.7 in) long), neck and legs. During the breeding season, the bill has a yellowish or orange-pink base and dark tip; the base is pink in winter. The legs are dark grey, brown or black. The sexes are similar,[8] but in breeding plumage, they can be separated by the male's brighter, more extensive orange breast, neck and head. In winter, adult black-tailed godwits have a uniform brown-grey breast and upperparts (in contrast to the bar-tailed godwit's streaked back). Juveniles have a pale orange wash to the neck and breast.[11]

In flight, its bold black and white wings and white rump can be seen readily. When on the ground it can be difficult to separate from the similar bar-tailed godwit, but the black-tailed godwit's longer, straighter bill and longer legs are diagnostic.[11][9] Black-tailed godwits are similar in body size and shape to bar-taileds, but stand taller.[8]

It measures 42 cm (17 in) from bill to tail with a wingspan of 70–82 cm (28–32 in).[8] Males weight around 280 g (9.9 oz) and females 340 g (12 oz).[12] The female is around 5% larger than the male,[8] with a bill 12–15% longer.[13]

The most common call is a strident weeka weeka weeka.

A study of black-tailed godwits in the Netherlands found a mortality rate of 37.6% in the first year of life, 32% in the second year, and 36.9% thereafter.[8] The oldest recorded, as of 8 November 2025[update], is 29 years 2 months, for a bird of the Icelandic subspecies L. l. islandica; it was colour ringed as a juvenile on 30 August 1996 on The Wash in Lincolnshire, England, and has subsequently been seen on a total of 91 occasions, including breeding in northern Iceland.[14]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]Black-tailed godwits have a discontinuous breeding range stretching from Iceland to the far east of Russia.[9] Their breeding habitat is river valley fens, floods at the edges of large lakes, damp steppes, raised bogs and moorlands. An important proportion of the European population now uses secondary habitats: lowland wet grasslands (with vegetation up to about 50 cm tall),[15] coastal grazing marshes, pastures, wet areas near fishponds or sewage works, and saline lagoons. Breeding can also take place in sugar beet, potato and rye fields in the Netherlands and Germany.[16]

In spring, black-tailed godwits feed largely in grasslands, moving to muddy estuaries after breeding and for winter.[16] On African wintering grounds, swamps, floods and irrigated paddy fields can attract flocks of birds. In India, inland pools, lakes and marshes are used, and occasionally brackish lakes, tidal creeks and estuaries.[8]

Godwits from the Icelandic population winter mainly in the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, and the Netherlands, though some fly on to Spain, Portugal, and perhaps Morocco.[17] Birds of the limosa subspecies from western Europe fly south to Morocco and then on to Senegal and Guinea-Bissau. Birds from the eastern European populations migrate to Tunisia and Algeria, then on to Mali or Chad.[18] Young birds from the European populations stay on in Africa after their first winter and return to Europe at the age of two years.[16] Asian black-tailed godwits winter in Australia, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea.

Black-tailed godwits are much more likely to be found on inland wetlands than the more coastal bar-tailed godwit. They migrate in flocks to western Europe, Africa, south Asia and Australia. Although this species occurs in Ireland and Great Britain all year-round, they are not the same birds. The breeding birds depart in autumn, but are replaced in winter by the smaller Icelandic race. These birds occasionally appear in the Aleutian Islands and, rarely, on the Atlantic coast of North America.

Behaviour

[edit]Breeding

[edit]

Black-tailed godwits are mostly monogamous; although it was not recorded in a four-year study of 50–60 pairs, bigamy was considered "probably frequent".[8] A study of the Icelandic population showed that despite spending winter apart, pairs are reunited on their breeding grounds within an average of three days of each other. If one partner does not arrive on time, 'divorce' occurs.[19] They nest in loose colonies. Unpaired males defend a temporary territory and perform display flights to attract a mate. Several nest scrapes are made away from the courtship territory, and are defended from other godwits. Once eggs are laid, an area of 30–50 m (98–164 ft) around the nest is defended.[8] The nest is a shallow scrape on the ground, usually in short vegetation.[20] The eggs may be hidden with vegetation by the incubating parent.[8]

The single brood of three to six eggs, coloured olive-green to dark brown,[8] measure 55 mm × 37 mm (2.2 in × 1.5 in) and weigh 39 g (1.4 oz) each (of which 6% is shell).[12] Incubation lasts 22–24 days and is performed by both parents. The young are downy and precocial and are brooded while they are small and at night during colder weather. After hatching, they are led away from the nest and may move to habitats such as sewage farms, lake edges, marshes and mudflats.[8] The chicks fledge after 25–30 days.[12]

Black-tailed godwit productivity varies, positively, with spring temperatures. However, during extreme events, such as a volcanic eruption, complete breeding failures can occur.[21]

Food and feeding

[edit]They mainly eat invertebrates, but also aquatic plants in winter and on migration. In the breeding season, prey includes beetles, flies, grasshoppers, dragonflies, mayflies, caterpillars, annelid worms and molluscs. Occasionally, fish eggs, frogspawn and tadpoles are eaten. In water, the most common feeding method is to probe vigorously, up to 36 times per minute, and often with the head completely submerged. On land, black-tailed godwits probe into soft ground and also pick prey items from the surface.[8]

Relationship to humans

[edit]In Europe, black-tailed godwits are only hunted in France, with the annual total killed estimated at 6,000 to 8,000 birds. This puts additional pressure on the western European population, and the European Commission has a management plan in place for the species in its member states.[22] In England, black-tailed godwits were formerly much prized for the table.[23] Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682) said: "[Godwits] were accounted the daintiest dish in England and I think, for the bignesse, of the biggest price." Old names included Blackwit,[23] Whelp, Yarwhelp, Shrieker, Barker and Jadreka Snipe.[24] The Icelandic name for the species is Jaðrakan.[12]

Status

[edit]There is an estimated global population of between 634,000 and 805,000 birds and estimated range of 7,180,000 square kilometres (2,770,000 sq mi).[9] In 2006 BirdLife International classified this species as Near Threatened due to a decline in numbers of around 25% in the previous 15 years.[1] It is also among the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies.[25] In 2024, L. limosa was listed as Endangered under the Australian EPBC Act.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2017) [amended version of 2016 assessment]. "Limosa limosa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017 e.T22693150A111611637. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-1.RLTS.T22693150A111611637.en.

- ^ "Limosa belgica". gbif.org. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 147.

- ^ Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode Contenant la Divisio Oiseaux en Ordres, Sections, Genres, Especes & leurs Variétés (in French and Latin). Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. Vol. 1, p. 48, Vol. 5, p. 261.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Sandpipers, snipes, coursers". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "Godwit". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o BWPi: The Birds of the Western Palearctic on interactive DVD-ROM. London: BirdGuides Ltd. and Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 978-1-898110-39-2.

- ^ a b c d e "Species factsheet: Limosa limosa". BirdLife International. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ Zhu, B.-R.; Verkuil, Y.I.; Conklin, J.R.; Yang, A.; Lei, W.; Alves, J.A.; Hassell, C.J.; Dorofeev, D.; Zhang, Z.; Piersma, T. (2021). "Discovery of a morphologically and genetically distinct population of Black-tailed Godwits in the East Asian-Australasian Flyway". Ibis. 163 (2): 448–462. doi:10.1111/ibi.12890.

- ^ a b Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter (1999). Collins Bird Guide. London: HarperCollins. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-00-219728-1.

- ^ a b c d Robinson, R.A. "Black-tailed Godwit Limosa limosa". BirdFacts. British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ Vinicombe, Keith. "Black-tailed and Bar-tailed Godwits". Articles. Birdwatch magazine. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ "29 and counting – Wash Wader Research Group". Wash Wader Research Group. 9 November 2025. Retrieved 11 November 2025.

- ^ Méndez, Verónica; Guðmundsson, Guðmundur A.; Skarphéðinsson, Kristinn H.; Katrínardóttir, Borgný; Auhage, Svenja; Þórisson, Böðvar; Ö. Snæþórsson, Aðalsteinn; Kolbeinsson, Yann; Þórarinsson, Þorkell L.; Stefánsson, Halldór W.; Helgason, Hálfdán H.; Þórarinsdóttir, Rán; Þórisson, Skarphéðinn G.; Gallo, Cristian; Alves, José A. (2025). "Predicting the breeding distribution of wader species across climatic and environmental gradients". Wildlife Biology (6) e01493. doi:10.1002/wlb3.01493. ISSN 1903-220X.

- ^ a b c Tucker, Graham M.; Heath, Melanie F. (1995). Birds in Europe: Their Conservation Status. BirdLife Conservation Series. Vol. 3. Cambridge: BirdLife International. pp. 272–273. ISBN 978-0-946888-29-0.

- ^ "About the species". Icelandic Godwits. Project Jaðrakan. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ "Black-tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa)". BirdGuides.com. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ "Icelandic birds rely on perfect timing". BBC News website. BBC. 3 November 2004. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ Gooders, John (1982). Collins British Birds. London: William Collins Sons & Co Ltd. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-00-219121-0.

- ^ Gunnarsson, T. G.; Jóhannesdóttir, L.; Alves, J. A.; Þórisson, B.; Gill, J. A. (2017). "Effects of spring temperature and volcanic eruptions on wader productivity" (PDF). Ibis. 159 (2): 467–471. doi:10.1111/ibi.12449.

- ^ "Management Plan for Black-tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa)" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ a b Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- ^ Greenoak, Francesca (1979). All The Birds Of The Air. Book Club Association.

- ^ "Limosa limosa: Black-tailed Godwit". AEWA birds. AEWA. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ "Limosa limosa — Black-tailed Godwit". Species Profile and Threats Database. Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. 5 January 2024. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

Further reading

[edit]Identification

[edit]- Vinicombe, Keith (1 January 2010). "Black-tailed and Bar-tailed Godwits". Birdwatch. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

Separation of limosa and islandica

[edit]- Roselaar, C.S.; Gerritsen, Gerrit J. (1991). "Recognition of Icelandic Black-tailed Godwit and its occurrence in the Netherlands" (PDF). Dutch Birding. 13 (4): 128–135.

- van Scheepen, Peter; Oreel, Gerald J. (1995). "Herkenning en voorkomen van Ijslandse Grutto in Nederland" [Identification and occurrence of Icelandic Black-tailed Godwit in the Netherlands] (PDF). Dutch Birding (in Dutch). 17 (2): 54–62.

- Evans, L.G.R. (July 2004). "Continental Black-tailed Godwit at College Lake – the first confirmed record for Buckinghamshire" (PDF). Rare Birds Weekly. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- Vinicombe, Keith (2005) A tale of two godwits Birdwatch 154:18-20

External links

[edit]- Black-tailed godwit species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 0.94 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- "Limosa limosa". Avibase.

- "Black-tailed godwit media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Black-tailed godwit photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Limosa limosa at IUCN Red List

- Audio recordings of Black-tailed godwit on Xeno-canto.

- Limosa limosa in Field Guide: Birds of the World on Flickr