From Wikipedia

Open on Wikipedia

| Sooty grouse | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Genus: | Dendragapus |

| Species: | D. fuliginosus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dendragapus fuliginosus (Ridgway, 1873)

| |

| |

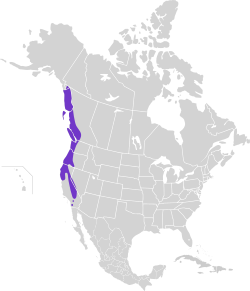

The sooty grouse (Dendragapus fuliginosus) is a species of forest-dwelling grouse native to North America's Pacific Coast Ranges.[2][3] It is closely related to the dusky grouse (Dendragapus obscurus), and the two were previously considered a single species, the blue grouse.[2][3][4]

Description

[edit]Adults have a long square tail, light gray at the end. Adult males are mainly dark with a yellow throat air sac surrounded by white, and a yellow wattle over the eye during display. Adult females are mottled brown with dark brown and white marks on the underparts.[3] Females have longer skinnier necks than males. The males have stouter bodies than the females.

Distribution and habitat

[edit]Their breeding habitat is the edges of conifer and mixed forests in mountainous regions of western North America, from southeastern Alaska and Yukon south to California.[3] Their range is closely associated with that of various conifers. They thrive in old forests because they need diverse plants and trees. Regenerated logged or burned areas also attract the sooty grouse as long as there are plenty of bushes and shrubs to nest in. The nest is a scrape on the ground concealed under a shrub or log.

Grouse mountain, a mountain that acts as the peak of Vancouver, Canada gets its name from the infamous blue grouse that lives on the mountain. The first hikers that reached the top of the mountain hunted the birds so they honored them by naming the mountain after them. This name is also attributed to the large population of the sooty grouse found on the mountain.

Migration

[edit]They are permanent residents but move short distances by foot and short flights to denser forest areas in winter, with the odd habit of moving to higher altitudes in winter.[2] The birds move from relatively open breeding areas in autumn to deep coniferous forests in the winter.

Taxonomy

[edit]The sooty grouse has four recognized subspecies:[5]

- D. f. fuliginosus (Ridgway, 1873)

- D. f. howardi (Dickey & Van Rossem, 1923)

- D. f. sierrae (Chapman, 1904)

- D. f. sitkensis (Swarth, 1921)

Diet

[edit]These birds forage on the ground, or in trees in winter. In winter, they mainly eat fir and douglas-fir needles, occasionally also hemlock and pine needles; in summer, other green plants (Pteridium, Salix), berries (Gaultheria, Mahonia, Rubus, Vaccinium), and insects (particularly ants, beetles, grasshoppers) are more important. In winter, they are capable of surviving on fir needles alone. In Spring, they enjoy a diet that consists more of berries, leaves, and flowers. Chicks are almost entirely dependent on insect food for their first ten days.[2] Like many birds, the sooty grouse eat grit and tiny stones. This helps them grind up food in the gizzard.

Breeding

[edit]Males sing with deep hoots on their territory and make short flapping flights to attract females. The sound sounds like someone is hitting a deep but quiet drum. The Males typically make these calls from high in the trees. Females leave the male's territory after mating. A female will then build her nest on the ground in a shallow hole protected by the covering of bushes or logs. She will then lay around 5 to 10 eggs. These eggs are well camouflaged due to their creamy base color with speckled brown spots.

Conservation

[edit]Sooty grouse are experiencing some population decline from habitat loss at the southern end of their range in southern California.[2] The status of the Sooty Grouse is now classified as at risk. Currently, the species is of low conservation concern, but if a decline in old-growth forests persists the risk of endangerment will increase.

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Dendragapus fuliginosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22734695A95095286. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22734695A95095286.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J., eds. (1994). Handbook of the Birds of the World 2: 401–402. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona ISBN 84-87334-15-6.

- ^ a b c d Sibley, D. (2000). The Sibley Guide to Birds. Knopf. pp. 143. ISBN 0-679-45122-6.

- ^ Banks, R. C.; Cicero, C.; Dunn, J. L.; Kratter, A. W.; Rasmussen, P. C.; Remsen, J. V. Jr.; Rising, J. D.; Stotz, D. F. (2006). "Forty-seventh Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-list of North American Birds" (PDF). The Auk. 123 (3): 926–936. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[926:FSTTAO]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2007-09-16.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Pheasants, partridges, francolins". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 13 October 2021.