Source: Wikipedia

| Black-throated tody-tyrant | |

|---|---|

| |

| From Cordillera del Cóndor, Ecuador | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Tyrannidae |

| Genus: | Hemitriccus |

| Species: | H. granadensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hemitriccus granadensis (Hartlaub, 1843)

| |

| |

The black-throated tody-tyrant (Hemitriccus granadensis) is a species of bird in the family Tyrannidae, the tyrant flycatchers. It is found in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela.[2]

Taxonomy and systematics

[edit]The black-throated tody-tyrant has a complicated taxonomic history. It was originally described in 1843 as Todirostrum granadense.[3] During the twentieth century it was successively placed in genera Euscarthmornis and Idiotilon, both of which were later merged into Hemitriccus.[4]

The black-throated tody-tyrant has these seven subspecies:[2]

- H. g. lehmanni (Meyer de Schauensee, 1945)

- H. g. intensus (Phelps, WH & Phelps, WH Jr, 1952)

- H. g. federalis (Phelps, WH & Phelps, WH Jr, 1950)

- H. g. andinus (Todd, 1952)

- H. g. granadensis (Hartlaub, 1843)

- H. g. pyrrhops (Cabanis, 1874)

- H. g. caesius (Carriker, 1932)

Some authors have suggested that more than one full species is represented within these seven taxa.[4][5][6]

Description

[edit]The black-throated tody-tyrant is 8.5 to 11 cm (3.3 to 4.3 in) long and weighs 6.5 to 8.5 g (0.23 to 0.30 oz). The sexes have the same plumage. Adults of the nominate subspecies H. g. granadensis have a dark olive crown. Their lores and wide eye-ring are whitish and their ear coverts grayish olive. Their back and rump are dark olive. Their wings are dark olive with indistinct yellow edges on the coverts. Their tail is dark dusky olive. Their upper throat and lower cheeks are sooty black and their lower throat whitish with grayish edges. They have a diffuse grayish band across the breast that fades to white on the lower breast and belly; their lower flanks and undertail coverts have a yellow tinge. All subspecies a black bill and gray to pinkish gray legs and feet. Most have a highly variable chestnut to pale orange iris.[7][8][9]

The other subspecies of the black-throated tody-tyrant differ from the nominate and each other thus:[7][8][9][10][11]

- H. g. lehmanni: brighter and more yellowish green crown and upperparts than nominate, with buff lores and eye-ring, brownish black throat, brownish wash on the breast, and sometimes a pale iris

- H. g. intensus: similar to lehmanni but blacker, less brownish, throat and a pure gray breast; paler iris than nominate

- H. g. federalis: whiter breast than nominate

- H. g. andinus: buffy lores and grayish (not solid gray) breast

- H. g. pyrrhops: tawny-buff to deep cinnamon eye-ring

- H. g. caesius: pale ashy gray, grayish white, or buffy white eye-ring; less extensive black on throat than nominate

Distribution and habitat

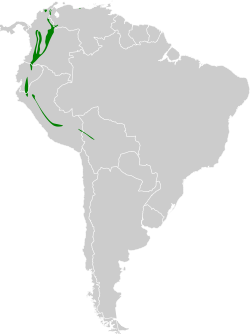

[edit]The black-throated tody-tyrant has a disjunct distribution. The subspecies are found thus:[7][8][9][10][11]

- H. g. lehmanni: isolated Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in northern Colombia

- H. g. intensus: Serranía del Perijá in Venezuela's Táchira state

- H. g. federalis: Venezuela's Federal District

- H. g. andinus: Norte de Santander and Santander departments in northeastern Colombia into Páramo de Tamá in western Táchira, Venezuela

- H. g. granadensis: all three Colombian Andes ranges except the northern end of the eastern; south into northern Ecuador to Carchi Province on the Andes' western slope and to Napo Province on the eastern slope

- H. g. pyrrhops: eastern slope of the Andes from Morona-Santiago Province, Ecuador, south to Cuzco Department, Peru

- H. g. caesius: from southeastern Peru's Puno Department into west-central Bolivia's La Paz and Cochabamba departments

The black-throated tody-tyrant inhabits humid montane forest, cloudforest, and shrubby regenerating areas in the subtropical and temperate zones. It often favors somewhat open areas such as forest edges and overgrown tree falls and landslide scars. In elevation it ranges between 1,500 and 3,500 m (4,900 and 11,500 ft) in Colombia, 1,700 and 3,000 m (5,600 and 9,800 ft) in Ecuador, 1,800 and 3,100 m (5,900 and 10,200 ft) in Peru, and 1,800 and 3,000 m (5,900 and 9,800 ft) in Venezuela.[7][8][9][10][11]

Behavior

[edit]Movement

[edit]The black-throated tody-tyrant is a year-round resident.[7]

Feeding

[edit]The black-throated tody-tyrant feeds on insects. It typically forages singly or in pairs, and occasionally joins mixed-species feeding flocks. It mostly forages in the forest's lower and middle levels. It mostly takes prey using short upward sallies from a perch to grab it from the underside of leaves.[7][8][9][11]

Breeding

[edit]The black-throated tody-tyrant's nesting season has not been fully defined but spans at least March to July in Colombia and includes December in Peru. Two nests in Colombia and one in Peru are known. They were "an enclosed “purse-like” pendant pouch inside of a moss ball suspended from a small branch with a side entrance and obscured by vegetation". One in each country had a single egg; in Colombia it was plain tan and in Peru bright white with a few red speckles. One egg was incubated for 19 days.[12] Nothing else is known about the species' breeding biology.[7]

Vocalization

[edit]As of early 2025 xeno-canto had many recordings of black-throated tody-tyrant vocalizations from Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru but only one from Bolivia and none from Venezuela.[13] The nominate subspecies gives a "short rattling trill, 'ti-ti-r-r-r-r-r-r'"[9] or a "fast trill"[8]. Other calls include "a gravelly 'dut’t’t, dut’t’t', a nasal 'tip-buuuuu' and sharp 'pik, peet, peet' ".[7] The vocalizations of subspecies other than H. g. pyrrhops are similar.[6] The song of H. g. pyrrhops is "a rising-falling, accelerating series of high, peeping notes: pup-pip-peep-peep'pip'pip'pip'pip' pip'pip". Its calls are "a rising or rising-falling, mewed weeb or weeble note; also a quiet, rapid popping trill".[10]

Status

[edit]The IUCN has assessed the black-throated tody-tyrant as being of Least Concern. It has a large range; its population size is not known and is believed to be decreasing. No immediate threats have been identified.[1] It is considered uncommon in Colombia and Peru and local in Ecuador.[8][9][10] In Venezuela it is "known from many specimens" in the Serranía del Perijá, is "locally fairly common" in southern Táchira, and known only from a few specimens in the Federal District.[11] It is considered "rare to uncommon, and somewhat local" in Bolivia. It occurs in several protected areas from Colombia to Peru.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2024). "Black-throated Tody-tyrant Hemitriccus granadensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2024: e.T22698941A264381654. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-2.RLTS.T22698941A264381654.en. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2024). "Tyrant flycatchers". IOC World Bird List. v 14.2. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ Guérin-Méneville, F.-É. (1843). Magasin de zoologie (in Latin). Vol. 6. Bureau de la revue zoologique. pp. 289–290. Retrieved January 27, 2025.

- ^ a b Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, G. Del-Rio, A. Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 18 November 2024. A classification of the bird species of South America. American Ornithological Society. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm retrieved November 26, 2024

- ^ Fitzpatrick, J. W. 2004. Family Tyrannidae (Tyrant-flycatchers). Pp. 170–462 in "Handbook of the Birds of the World, Vol. 9. Cotingas to Pipits and Wagtails." (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliot, and D. A. Christie, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

- ^ a b Boesman, P. (2016). "HBW Alive Ornithological Note 249: Notes on the vocalizations of Black-throated Tody-tyrant (Hemitriccus granadensis)". Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved January 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Clock, B. M. and G. M. Kirwan (2020). Black-throated Tody-Tyrant (Hemitriccus granadensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.btttyr1.01 retrieved January 27, 2025

- ^ a b c d e f g McMullan, Miles; Donegan, Thomas M.; Quevedo, Alonso (2010). Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia. Bogotá: Fundación ProAves. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-9827615-0-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ridgely, Robert S.; Greenfield, Paul J. (2001). The Birds of Ecuador: Field Guide. Vol. II. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 481–482. ISBN 978-0-8014-8721-7.

- ^ a b c d e Schulenberg, T.S.; Stotz, D.F.; Lane, D.F.; O'Neill, J.P.; Parker, T.A. III (2010). Birds of Peru. Princeton Field Guides (revised and updated ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 430. ISBN 978-0691130231.

- ^ a b c d e Hilty, Steven L. (2003). Birds of Venezuela (second ed.). Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 592.

- ^ McCullough, J. M.; Londoño, G. A. (2017). "Nesting biology of the Black-throated Tody-Tyrant (Hemitriccus granadensis) with notes on mating displays". Wilson Journal. 129 (4): 820–826. Retrieved January 27, 2025.

- ^ "Black-throated Tody-Tyrant Hemitriccus granadensis". Xeno-canto. 2025. Retrieved January 27, 2025.

External links

[edit] Media related to Hemitriccus granadensis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hemitriccus granadensis at Wikimedia Commons