From Wikipedia

Open on Wikipedia

| Brown-chested martin | |

|---|---|

| In Argentina | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Hirundinidae |

| Genus: | Progne |

| Species: | P. tapera

|

| Binomial name | |

| Progne tapera (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

| |

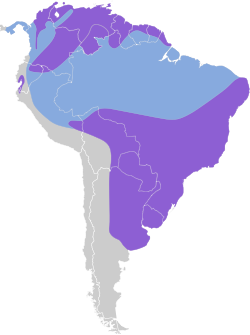

| Year-round Non-Breeding | |

| Synonyms | |

|

See text | |

The brown-chested martin (Progne tapera) is a species of passerine bird in the family Hirundinidae, the swallows and martins.[2] It is found regularly in Panama and every mainland South American country except Chile.[3][4] It has been documented as a vagrant in Aruba and Chile and there are unconfirmed reports from the Falkland Islands.[4] It is a casual visitor to Costa Rica[5] and has been recorded in Florida[6], Massachusetts[7], and New Jersey[8].

Taxonomy and systematics

[edit]The brown-chested martin was originally described in 1766 as Hirundo Tapera.[9] It was later moved to genus Progne that had been erected in 1826.[2] However, for much of the twentieth century it was placed by itself in genus Phaeoprogne before being restored to its present Progne.[10]

The brown-chested martin has two subspecies, the nominate P. t. tapera (Linnaeus, 1766) and P. t. fusca (Vieillot, 1817).[2]

Description

[edit]The brown-chested martin is 16 to 18 cm (6.3 to 7.1 in) long and weighs 30 to 40 g (1.1 to 1.4 oz).[11][12] The sexes have the same plumage. Adults of the nominate subspecies have a mostly sandy brown head with a white chin and throat. Their upperparts are sandy brown. Their tail is slightly forked; it and their wings are a darker brown than the upperparts. Their underparts are mostly white with an indistinct brown band across the breast. Subspecies P. t. fusca is larger and overall darker than the nominate with a more defined breast band and dusky markings on the lower breast and belly. Juveniles have a more squared tail than adults and a grey-brown wash on the sides of the throat.[11]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The nominate subspecies of the brown-chested martin is found from northern and eastern Colombia east through Venezuela, the Guianas, and far northern and northeastern Brazil and separately on the west side of the Andes from Los Ríos Province in southwestern Ecuador south into northwestern Peru's Tumbes Department.[11][12] The range of subspecies P. t. fusca overlaps that of the nominate. It is found in Panama and throughout South America east of the Andes as far south as La Pampa and Buenos Aires provinces in Argentina.[11]

The brown-chested martin inhabits semi-open to open landscapes such as grasslands, cultivated areas, clearings in forest, and human settlements. It favors areas near water.[11] In Venezuela the nominate is found below 1,000 m (3,300 ft); subspecies P. t. fusca is found mostly below 400 m (1,300 ft) but has sight records up to 1,900 m (6,200 ft).[13] The species reaches 2,500 m (8,200 ft) in Colombia and 600 m (2,000 ft) in Ecuador and Peru.[14][12][15]

Behavior

[edit]Movement

[edit]The nominate subspecies of the brown-chested martin is a year-round resident throughout its range. Subspecies P. t. fusca is a partial migrant. Populations to the south of a line approximately from southern Bolivia to the Atlantic in Brazil's São Paulo state move north for the austral winter, spreading out over central and northern South America and into Panama. (Note that the map does not show this southern area as a breeding-only range.) In migration and in its winter range it forms flocks that can exceed 100,000 individuals.[3][11]

Feeding

[edit]The brown-chested martin feeds on a wide variety of insects captured in mid-air.[11] A population in São Paulo fed mostly on winged ants and termites.[16] It forages singly or in small flocks, flying fast and low over vegetation and water and more slowly among trees and over open land. It also flies higher when feeding in swarms of flying ants and termites.[11]

Breeding

[edit]The brown-chested martin's breeding season has not been fully defined but spans April to June in Venezuela, March to May in Colombia, and November to March in the far south. It nests solitarily or in small loose colonies, using cavities in earthen banks, termite nests, trees, and human structures such as bridges and buildings. Subspecies P. t. fusca often uses old rufous hornero (Furnarius rufus) nests. The species builds a nest from dry grass lined with feathers in the cavity. The usual clutch is four eggs though three to five are common. The female alone incubates, for 14 to 15 days. Fledging occurs about 28 days after hatch and both parents provision nestlings.[11]

Vocalization

[edit]The brown-chested martin's song is "harsh and guttural with [a] series of gurgling sounds".[11] It has been described in more detail as "a series of liquid, rolling, descending trills, for example trr-tee-tuk-TEEERRR...trr-tee-tuk-TEEERRR...". Its calls are "a dry, buzzy djzeut and a more musical dureet".[15]

Status

[edit]The IUCN has assessed the brown-chested martin as being of Least Concern. It has an extremely large range; its estimated population of at least fifty million mature individuals is believed to be decreasing. No immediate threats have been identified.[1] It is considered common in Colombia[14] and uncommon in Ecuador[11]. The resident nominate subspecies is uncommon in Peru and the status of the migratory P. t. fusca there is not well known.[15] The nominate subspecies is "not numerous" in Venezuela; fusca is "widespread in lowlands" and "locally abundant" elsewhere.[13] It is considered "common to frequent" in Brazil.[17] "Large flocks roosting on buildings are sometimes considered a nuisance by local human inhabitants."[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2020). "Brown-chested Martin Progne tapera". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T22712092A137688210. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22712092A137688210.en. Retrieved 21 January 2026.

- ^ a b c Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (March 2025). "Swallows". IOC World Bird List. v 15.1. Retrieved 17 December 2025.

- ^ a b Check-list of North American Birds (7th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union. 1998. p. 456.

- ^ a b Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, D. F. Lane, L, N. Naka, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 29 November 2025. Species Lists of Birds for South American Countries and Territories. South American Classification Committee associated with the International Ornithologists' Union. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCCountryLists.htm retrieved November 30, 2025

- ^ Garrigues, Richard; Dean, Robert (2007). The Birds of Costa Rica. Ithaca: Zona Tropical/Comstock/Cornell University Press. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-0-8014-7373-9.

- ^ "Official Florida State Bird List". Florida Ornithological Society. July 2024. Retrieved January 21, 2026.

- ^ Marshall Iliff; et al. (October 2024). "Official State List". Massachusetts Avian Records Committee. Retrieved January 21, 2026.

- ^ Larson, Laurie; Hanson, Jennifer W.; Boyle, Bill (December 2025). "New Jersey State List" (PDF). New Jersey Bird Records Committee. Retrieved January 21, 2026.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1766). Caroli a Linné ... Systema naturae: per regna tria natura, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. I. Impensis direct. Laurentii Salvii. p. 345. Retrieved January 21, 2026.

- ^ Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, D. F. Lane, L, N. Naka, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 29 November 2025. A classification of the bird species of South America. South American Classification Committee associated with the International Ornithologists' Union. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm retrieved November 30, 2025

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Turner, A. (2025). Brown-chested Martin (Progne tapera), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, E. de Juana, and F. Medrano, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.brcmar1.01.1 retrieved January 21, 2026

- ^ a b c Ridgely, Robert S.; Greenfield, Paul J. (2001). The Birds of Ecuador: Field Guide. Vol. II. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 581. ISBN 978-0-8014-8721-7.

- ^ a b Hilty, Steven L. (2003). Birds of Venezuela (second ed.). Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 684.

- ^ a b McMullan, Miles; Donegan, Thomas M.; Quevedo, Alonso (2010). Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia. Bogotá: Fundación ProAves. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-9827615-0-2.

- ^ a b c Schulenberg, T.S.; Stotz, D.F.; Lane, D.F.; O'Neill, J.P.; Parker, T.A. III (2010). Birds of Peru. Princeton Field Guides (revised and updated ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 512. ISBN 978-0691130231.

- ^ Oniki-Willis, Yoshika; Willis, Edwin O.; Machado, Vera Ligia Letizio; Lopes, Leonardo Esteves (2022-03-30). "Diet of two coexisting martins (Passeriformes: Hirundinidae) from southeastern Brazil". Ornithology Research. 30 (2): 130–134. Bibcode:2022OrniR..30..130O. doi:10.1007/s43388-022-00092-3. hdl:11449/234339. ISSN 2662-673X. S2CID 258704402.

- ^ van Perlo, Ber (2009). A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 342–343. ISBN 978-0-19-530155-7.